With Malice Towards None

With Malice Toward None: The Role Of Civics Education In The 2020 Election

Amidst the battles still raging across the nation in the aftermath of the elections, the historic words enunciated by President Lincoln in his second inaugural address in 1865 seem most apropos.

Amidst the battles still raging across the nation in the aftermath of the elections, the historic words enunciated by President Lincoln in his second inaugural address in 1865 seem most apropos.

“With malice toward none; with charity for all;

With firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in;

To bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace among ourselves…”

How many of us have ever read these words, have ever studied their cause and origins, other than (maybe) just knowing there was a civil war?

Lincoln spoke at a time of distrust, rancor, stereotyping and yes, even hatred, a time like today. So now the election appears to be over, but how might the distrust and vitriol that has so infected our civic life of late recede? It turns out that history is our guide. Our history – one that is rarely taught, dissected or relished.

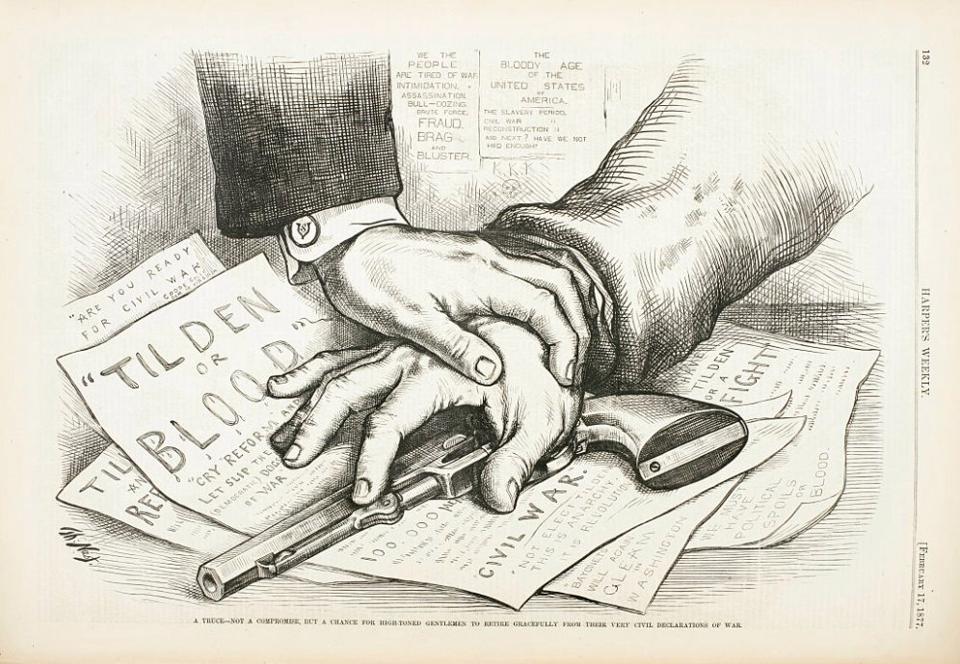

The election of 1800 had to go to the Congress for resolution. In 1824, the House also had to decide the vote, and accusations of corruption and being on the verge of monarchy were loud and common. We progressed to fight the battle over slavery and states’ rights that were the focus of that election. The year 1876 would also deeply split our nation. “Disputed returns and secret back-room negotiations put Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House—and Democrats back in control of the South.” Social unrest has often shaped our nation. Anyone who witnessed or studied the 1970s Vietnam War protests remembers students shot on a college campus, defense research labs blown up with innocent people in them, and regular violence in the streets of major American cities.

Our nation has been through what we are experiencing today and far worse and emerged intact. While we’re not where any of us want to be, history is a guide to correction, potential and promise. History can quell the passions and move us forward.

“History also injects the realization that it isn’t just behind us, it’s right now and it’s going to be tomorrow, and that we are going to be judged by history. … How will we measure up?” argues the famed author and historian David McCullough.

While we can’t predict or control the actions of our politicians, we can – and must – direct how and what we teach kids about our country and its resilience.

Mounds of data collected over decades show the magnitude of the job. According to The Nation’s Report Card issued by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, only 24 percent of American students perform at or above proficiency levels in civics, up just two percent from 1998. “In 2018, the average U.S. history score for eighth-grade students was 4 points lower compared to 2014,” and that was already low. Just fifteen percent – that’s one-five – of eighth graders were proficient in history. For students of color it was between five and eight percent! These data were the same for students a generation ago, today’s adult citizens.

Progress is also impeded by a lack of knowledge about who precisely is in charge of helping citizens achieve their ideals, and how. A 2019 study by The Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only 39 percent of Americans could name all three branches of our federal government, while 37 percent could not name a single right, not one, guaranteed by the Constitution’s First Amendment. Only nine states and the District of Columbia require one year of U.S. government or civics at the high school level. Another nine states require students to take the same test given to applicants for citizenship. The citizenship test should be mandatory in all 50.

How many students will never have that great history teacher to give them perspective? How many will never know what the fuss is all about, or why our framers resolved to create a bond that would move us “toward a more perfect union?” Understanding America’s at times rough-and-tumble history is essential to seeing a way forward.

It took the modern hit stage play Hamilton to introduce millions to the true influence of one founding father, whose life ended in a duel with the sitting vice president of the United States. Art is a wonderful thing. But it’s not a substitute for knowledge.

“History also injects the realization that it isn’t just behind us, it’s right now and it’s going to be tomorrow, and that we are going to be judged by history. … How will we measure up?” argues the famed author and historian David McCullough.

While we can’t predict or control the actions of our politicians, we can – and must – direct how and what we teach kids about our country and its resilience.

Mounds of data collected over decades show the magnitude of the job. According to The Nation’s Report Card issued by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, only 24 percent of American students perform at or above proficiency levels in civics, up just two percent from 1998. “In 2018, the average U.S. history score for eighth-grade students was 4 points lower compared to 2014,” and that was already low. Just fifteen percent – that’s one-five – of eighth graders were proficient in history. For students of color it was between five and eight percent! These data were the same for students a generation ago, today’s adult citizens.

Progress is also impeded by a lack of knowledge about who precisely is in charge of helping citizens achieve their ideals, and how. A 2019 study by The Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only 39 percent of Americans could name all three branches of our federal government, while 37 percent could not name a single right, not one, guaranteed by the Constitution’s First Amendment. Only nine states and the District of Columbia require one year of U.S. government or civics at the high school level. Another nine states require students to take the same test given to applicants for citizenship. The citizenship test should be mandatory in all 50.

How many students will never have that great history teacher to give them perspective? How many will never know what the fuss is all about, or why our framers resolved to create a bond that would move us “toward a more perfect union?” Understanding America’s at times rough-and-tumble history is essential to seeing a way forward.

It took the modern hit stage play Hamilton to introduce millions to the true influence of one founding father, whose life ended in a duel with the sitting vice president of the United States. Art is a wonderful thing. But it’s not a substitute for knowledge.

Education is the key to a safe, secure, and civilized society. Great education is the key to understanding why this nation, what Abraham Lincoln called “the last best hope of earth,” is worth fighting over, and fighting for.

You can’t love what you do not know, McCullough says. Our children must come to know America so they may be inspired to do their part someday to heal our current divisions. An absence of malice and an abundance of charity can work wonders. We must show the power of that idea to our kids through teaching history.

The divisions are bound to continue. But understanding history is a sure way to bridge the divide. That doesn’t mean giving in to policies or practices with which you disagree or which are against your moral principles. It does mean seeking to understand, to debate, advocate and even argue, with civility, respect and above all, knowledge.

That’s what a great education can do for our kids. Let’s help them ask “Why America?” to move the needle on that more perfect union. Let’s help them achieve education excellence so they understand the roles and responsibilities that come with citizenship. That’s how America can move forward. With malice toward none.

You can’t love what you do not know, McCullough says. Our children must come to know America so they may be inspired to do their part someday to heal our current divisions. An absence of malice and an abundance of charity can work wonders. We must show the power of that idea to our kids through teaching history.

The divisions are bound to continue. But understanding history is a sure way to bridge the divide. That doesn’t mean giving in to policies or practices with which you disagree or which are against your moral principles. It does mean seeking to understand, to debate, advocate and even argue, with civility, respect and above all, knowledge.

That’s what a great education can do for our kids. Let’s help them ask “Why America?” to move the needle on that more perfect union. Let’s help them achieve education excellence so they understand the roles and responsibilities that come with citizenship. That’s how America can move forward. With malice toward none.

Founded in 1993, the Center for Education Reform aims to expand educational opportunities that lead to improved economic outcomes for all Americans — particularly our youth — ensuring that conditions are ripe for innovation, freedom and flexibility throughout U.S. education.