Home » News & Analysis » Commentary » A Teachable Moment: Deep And Rich Education Is Vital To Bringing Out Our Better Angels

A Teachable Moment: Deep And Rich Education Is Vital To Bringing Out Our Better Angels

Learning in the wake of chaos and insurrection

January 12, 2021

By Jeanne Allen, Founder and CEO of CER

By Jeanne Allen, Founder and CEO of CER

High school American Government teacher Mrs. Feldman had a profound impact on me and my class, ensuring not only that we would become steeped in our nation’s history, but passionate too. We flocked to her at a recent reunion, and it struck me then that we who all grew to have divergent viewpoints never knew hers. Similarly, “Little” Miss Mahoney (because there was a taller one in the school) taught us to relish great literature, to analyze and to dig into what was written and why. Whether we were reading The Bell Jar, The Fountainhead, Of Mice and Men or Catcher in the Rye, she demanded tolerance and fortitude in the pursuit of knowledge.

I was similarly inspired in college. With a diverse cadre of fans and followers to this day, Professor Hickok led us to demonstrate the basis for all we said and wrote, by grounding us in the copious teachings that exist from the earliest days of our Republic. Dr. Friedman caused my love of political philosophy and pushed me to pursue my youthful passion for justice on Capitol Hill.

Arriving to do just that, and encouraged by these profound experiences, I went to work handling at first the most mundane (including sweeping, mail duty, phones and carry out) and later the most serious of tasks (including prepping the boss on the MX missile, social security and education). From stints with Congressman Florio, a Democrat, to Congresswoman Roukema, a Republican, I traveled the corridors of Capitol Hill, seeing the debates and sometimes the rancor give way to congenial bi-partisan Friday happy hours, with many traversing the lounges together from the Capitol Hill Club (for Republicans) to the Democratic Club (self-explanatory). Without fear of cell phones and cameras, members of Congress publicly and proudly showed up at all of the haunts young people would frequent, crossing the aisle, after hours. They were models. We were smitten by them all, and proud.

Without regard for point of view, everything from seeing a license plate with a 1 Maryland, or a 5 California to walking the halls of the Capitol was cause for excitement. Ceremonies elicited tears. Every action was another key to how we govern, why it mattered.

Later while working at the U.S. Department of Education, when Republicans led the White House and Democrats the Senate, I will never forget standing at the door to a meeting I organized for Historically Black Colleges and Universities. As I directed U.S. Senators to their places, in walked polar opposites together, South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond and Delaware’s Joe Biden, chatting, with a kind hello to a lowly staffer, and a jovial exchange as they took their seats.

I was similarly inspired in college. With a diverse cadre of fans and followers to this day, Professor Hickok led us to demonstrate the basis for all we said and wrote, by grounding us in the copious teachings that exist from the earliest days of our Republic. Dr. Friedman caused my love of political philosophy and pushed me to pursue my youthful passion for justice on Capitol Hill.

Arriving to do just that, and encouraged by these profound experiences, I went to work handling at first the most mundane (including sweeping, mail duty, phones and carry out) and later the most serious of tasks (including prepping the boss on the MX missile, social security and education). From stints with Congressman Florio, a Democrat, to Congresswoman Roukema, a Republican, I traveled the corridors of Capitol Hill, seeing the debates and sometimes the rancor give way to congenial bi-partisan Friday happy hours, with many traversing the lounges together from the Capitol Hill Club (for Republicans) to the Democratic Club (self-explanatory). Without fear of cell phones and cameras, members of Congress publicly and proudly showed up at all of the haunts young people would frequent, crossing the aisle, after hours. They were models. We were smitten by them all, and proud.

Without regard for point of view, everything from seeing a license plate with a 1 Maryland, or a 5 California to walking the halls of the Capitol was cause for excitement. Ceremonies elicited tears. Every action was another key to how we govern, why it mattered.

Later while working at the U.S. Department of Education, when Republicans led the White House and Democrats the Senate, I will never forget standing at the door to a meeting I organized for Historically Black Colleges and Universities. As I directed U.S. Senators to their places, in walked polar opposites together, South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond and Delaware’s Joe Biden, chatting, with a kind hello to a lowly staffer, and a jovial exchange as they took their seats.

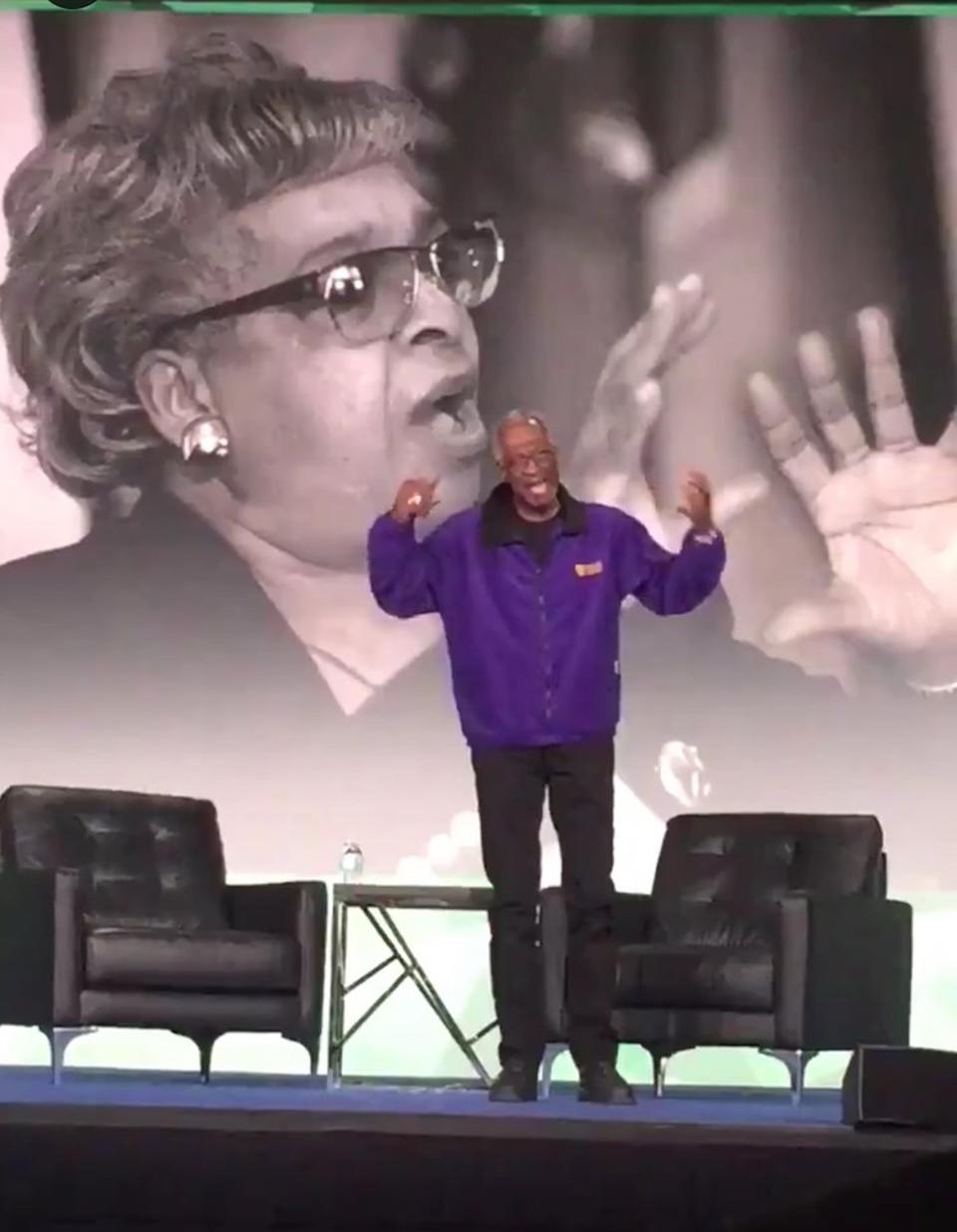

The ability of people from different walks of life to find common ground has been a feature in years past in both Washington and the States. Republican Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson and Democratic State Representative Polly Williams,once a black panther, and former Milwaukee Superintendent Dr. Howard Fuller waged a battle together to give poor kids educational choice. Similarly in Ohio, the work of Republican George Voinovich and Democratic City Councilwoman Fannie Lewis to create the Cleveland Scholarship program traveled all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. “We were losing 50% of our end product and it was time to stop the hemorrhaging,” Lewis said. “And when I read an article about choice it was the thing I made up my mind to become a part of.” She never looked at political affiliation as a driver or obstacle.

Howard Fuller in 2018 tells the audience at the Foundation for Excellence in Education’s National Summit on Education Reform about Williams’s early role and influence in the parental school choice movement. HOWARD FULLER / THE 74

Left to right to center, from California to Minnesota to New Jersey, innovations in educational policy – from performance pay, to standards to charter schools and choice, to blended learning and microschools – all have made a difference in students’ lives because diverse but principled people came together.

Such relationships and recollections make me hopeful for the future. The 1/6 insurrection at the Capitol was like a collective gut punch, and I like many, took it personally. The beauty of the building, its symbolism as a fortress for freedom, of an evolving, imperfect nation whose people must be bound by their common commitment to its principles and govern collectively across their differences were all under attack, as was the place that forged my past, and my future.

As the events unfolded, it was unclear who was in charge and what was happening, limited by what we could see on TV or social media. Rumors abounded. Hours and days after, we are still coming to know the full truth about the assault on our nation, made all the more pernicious and evil by the intentions of the perpetrators, people whose beliefs undermine everything this nation stands for, and everything that I have been taught, learned and believe about what is right and just.

The nation’s founders believed that education would provide young people the knowledge, capacities, and ethics required to protect liberty from arbitrary power, according to Richard Brown, author of The Strength of a People, The Idea of an Informed Citizenry in America. They believed only an enlightened people could sustain self government. The words of Thomas Jefferson are particularly prescient after last week’s mob on display:

“Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone. The people themselves therefore are its only safe depositories. And to render even them safe, their minds must be improved to a certain degree.” We must educate everyone “regardless of wealth, birth and or other accidental condition.”

But we’ve failed on realizing that vision and it shows. Our education system is inequitable and results uneven. Among U.S. eighth-graders, more than three-quarters are below proficiency in civics, a fact that should frighten every American. By the time our students reach adulthood, they have scant knowledge about how our nation is governed. Hatred is borne of ignorance and ignorance festers when we fail to impart knowledge.

Arthur Levine, former president of Teachers College, Columbia University and of the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation argues that “we lack the deep understanding of history and its importance to be the knowledgeable participants in the American citizenry so many seek.”

“So what do we do when only 13 percent of Americans know when the U.S. Constitution was ratified?” Levine posits. “Or when six in 10 don’t know which countries the United States fought in World War II? Or when less than a quarter of Americans know why we fought the British during the Revolutionary War? Identifying our collective educational shortcomings is not an attempt to embarrass the American people or to insult our national intelligence. It is, though, a clarion call for why we need to do better when it comes to the teaching, and learning, of American history.”

The data and our experiences as of late are indeed a clarion call for a renaissance in education, one that demands the fine training of hearts and minds, with the accumulation of knowledge through great literature, history, and philosophy, for everyone. We must inspire students and give them access to the best in-class teaching, wherever it exists, whoever is doing it, no matter what the school model or source. Our nation needs engaged instructors who are rigorously honest about the nation’s past and passionately optimistic about its best days and accomplishments. They must learn its foundation, wars and struggles. They must have access to knowledge and debate, not compromised or cancelled because it represents one point of view, a practice Forbes Editor Randall Lane aptly calls “a societal blight.”

This is a time for cooperation and finding common ground on education as much as in political affairs. An education that is both deep and rich brings with it the understanding that diversity of thought and love of country can co-exist peacefully, and that our darkest days can yield to our better angels. That’s where we must begin anew.

Such relationships and recollections make me hopeful for the future. The 1/6 insurrection at the Capitol was like a collective gut punch, and I like many, took it personally. The beauty of the building, its symbolism as a fortress for freedom, of an evolving, imperfect nation whose people must be bound by their common commitment to its principles and govern collectively across their differences were all under attack, as was the place that forged my past, and my future.

As the events unfolded, it was unclear who was in charge and what was happening, limited by what we could see on TV or social media. Rumors abounded. Hours and days after, we are still coming to know the full truth about the assault on our nation, made all the more pernicious and evil by the intentions of the perpetrators, people whose beliefs undermine everything this nation stands for, and everything that I have been taught, learned and believe about what is right and just.

The nation’s founders believed that education would provide young people the knowledge, capacities, and ethics required to protect liberty from arbitrary power, according to Richard Brown, author of The Strength of a People, The Idea of an Informed Citizenry in America. They believed only an enlightened people could sustain self government. The words of Thomas Jefferson are particularly prescient after last week’s mob on display:

“Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone. The people themselves therefore are its only safe depositories. And to render even them safe, their minds must be improved to a certain degree.” We must educate everyone “regardless of wealth, birth and or other accidental condition.”

But we’ve failed on realizing that vision and it shows. Our education system is inequitable and results uneven. Among U.S. eighth-graders, more than three-quarters are below proficiency in civics, a fact that should frighten every American. By the time our students reach adulthood, they have scant knowledge about how our nation is governed. Hatred is borne of ignorance and ignorance festers when we fail to impart knowledge.

Arthur Levine, former president of Teachers College, Columbia University and of the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation argues that “we lack the deep understanding of history and its importance to be the knowledgeable participants in the American citizenry so many seek.”

“So what do we do when only 13 percent of Americans know when the U.S. Constitution was ratified?” Levine posits. “Or when six in 10 don’t know which countries the United States fought in World War II? Or when less than a quarter of Americans know why we fought the British during the Revolutionary War? Identifying our collective educational shortcomings is not an attempt to embarrass the American people or to insult our national intelligence. It is, though, a clarion call for why we need to do better when it comes to the teaching, and learning, of American history.”

The data and our experiences as of late are indeed a clarion call for a renaissance in education, one that demands the fine training of hearts and minds, with the accumulation of knowledge through great literature, history, and philosophy, for everyone. We must inspire students and give them access to the best in-class teaching, wherever it exists, whoever is doing it, no matter what the school model or source. Our nation needs engaged instructors who are rigorously honest about the nation’s past and passionately optimistic about its best days and accomplishments. They must learn its foundation, wars and struggles. They must have access to knowledge and debate, not compromised or cancelled because it represents one point of view, a practice Forbes Editor Randall Lane aptly calls “a societal blight.”

This is a time for cooperation and finding common ground on education as much as in political affairs. An education that is both deep and rich brings with it the understanding that diversity of thought and love of country can co-exist peacefully, and that our darkest days can yield to our better angels. That’s where we must begin anew.

Founded in 1993, the Center for Education Reform aims to expand educational opportunities that lead to improved economic outcomes for all Americans — particularly our youth — ensuring that conditions are ripe for innovation, freedom and flexibility throughout U.S. education.